Beyond the Headlines: China’s Real Role in Mexico’s Wealth Production

By Maggie Switek, NCF24 Fellow; senior director of the Milken Institute’s Research Department

In May of this year, the US administration increased tariffs on imports of Chinese strategic products such as semiconductors, electric vehicles, and critical minerals. This action was followed by a wave of speculations on the likelihood of a shift of production from China to countries not subject to the tariffs—principally Mexico—allowing Chinese manufacturers to ship goods to the US while avoiding tariffs. Concerns about the growth of Chinese investments and production in the US’s regional trade partners have been on the rise, accelerating after Mexico became the main source of imports of goods into the US in 2023. With millions of US jobs supported by North American trade Mexico is a keystone country for Washington, which explains the US’s unease about the possibility of its main trade partner strengthening its relations with China.

While these concerns are based on important recent trends (showing growth in Chinese capital inflows to Mexico) they often fail to consider the still relatively small share of Mexico’s total investments originating in China and the broad historical context. To fully grasp the role played by China, relative to North America and other Asian countries, in Mexico’s economy requires comparing the magnitudes of capital inflows by origin, importance to production, and the history of Mexico’s relationships with these countries and regions. A broad overview of these manifold aspects suggests that, while growing, China’s role in Mexico’s wealth production remains limited in comparison to that played by North America and its other key partners.

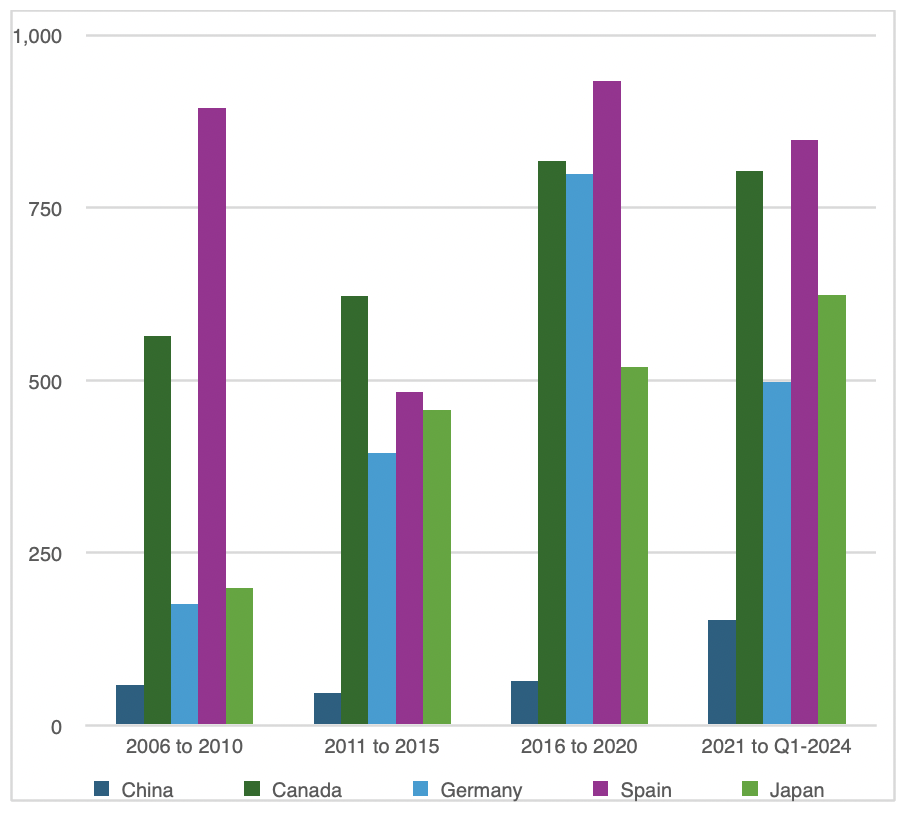

As mentioned above, inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) from China (including mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan) to Mexico are growing. Chinese quarterly investments in Mexico averaged $64.5 million between 2016 and 2020, while by 2021 to 2024(Q1), they had risen to an average of $153.5 million. This remarkable growth, however, has come at a time of rising investments in Mexico from all sources. Because of this, the increase in Chinese investments as a share of Mexico’s FDI has been slower than the growth of total value, which coupled with its low starting level makes the rise of Chinese capital flowing into Mexico less remarkable.

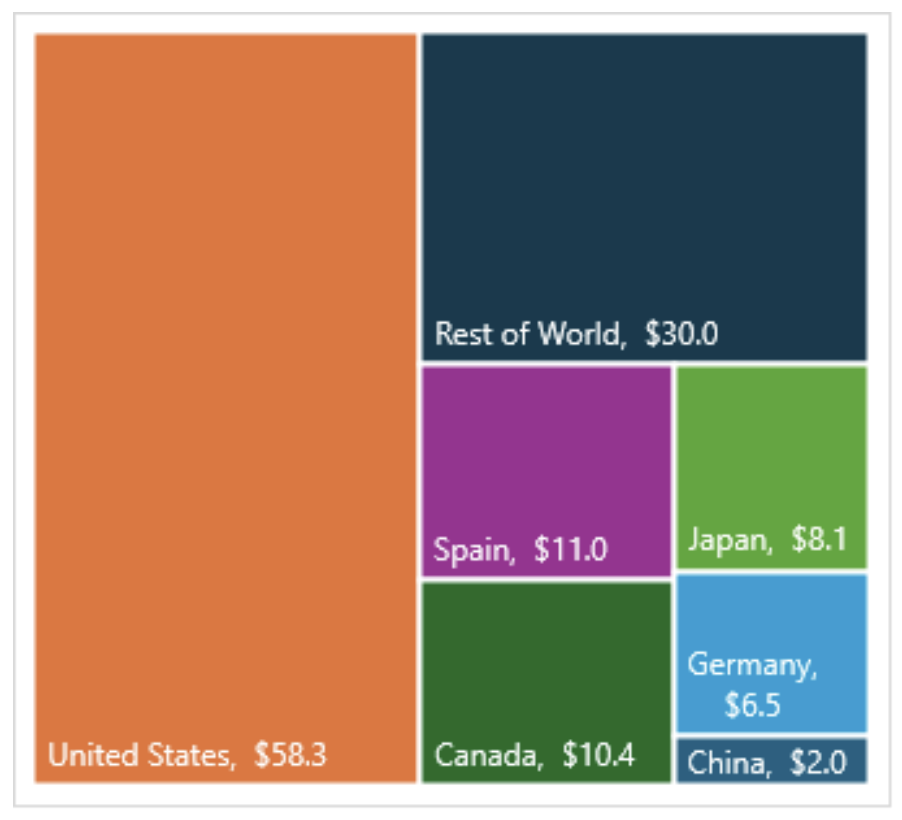

Mexico’s FDI since 2021, by Origin (billions of USD) Average Quarterly FDI to Mexico (millions of USD)

Since 2021, the US has invested $58.3 billion in Mexico, dwarfing the $2.0 billion foreign direct investment from China. But it doesn’t take a comparison to Mexico’s main global partner to overshadow the size of Chinese investments. After the US, Mexico’s biggest investors are Spain and Canada, with their total FDI flows to Mexico since 2021 amounting to $11.0 billion and $10.4 billion, respectively. Japan is Mexico’s third-largest investor and the biggest Asian source of foreign direct investment. This Asian Tiger also has a longer history of investing in Mexico than China. In the 2010s, Mexico experienced a similar growth in capital inflows from Japan as it is seeing today from China, with Japan’s average quarterly investment in Mexico more than doubling from 2011 to 2015, compared to the prior five-year period. Since 2021, Japan’s quarterly investments have averaged $623 million, or $470 million more than those from China.

While this does not diminish the importance of the growing Chinese investments in Mexico, it does provide some much-needed context. Based on project announcements, capital inflows from China to Mexico are expected to continue to rise. Overall, Mexico has experienced a historic rise in FDI project announcements, with notices of new projects exceeding $40 billion in 2022 after more than doubling from the prior year. This sets Mexico apart from other Latin American countries such as Brazil, whose project announcements totaled about $18 billion in the same year. China has played an important role in Mexico’s rise in planned capital inflows, ranking fourth in expectations of new investments according to data compiled by Secretaría de Economía in February of 2024. Still, from January to mid-March of 2024, China’s project announcements represented only 6 percent of the total $31.5 million in Mexico’s new projects, trailing the US, Germany, and Argentina, whose project announcements constituted 57 percent, 17 percent, and 14 percent of the total, respectively.

It is also important to remember that goods assembled and produced in Mexico have a substantial North American value-added, regardless of the source of capital. Consider for example the production in Hofusan Industrial Park, one of the largest Chinese-Mexican industrial parks. According to Yu Ken Wei, the general manager of Man Wah Furniture factory (which produces goods sold in the US), the company hopes to employ more than 1,200 Mexican workers in the coming years. While some consider these types of production as an attempt by Chinese firms to use Mexico as a backdoor into the US, the goods produced in Mexico are largely made by Mexicans working with (according to Yu Ken Wei) relatively high productivity levels. Based on recent estimates, Mexico’s exports have about 65 percent of domestic value-added, with another 13 percent of value-added from the US and Canada. This suggests that Mexico’s exports contain more than three-fourths of North American value. While there is considerable variation depending on industry, type of good, and (likely) source of capital, the fact remains that products made in Mexico “are, to all intends and purposes, Mexican,” as expressed by Mexico’s former vice-minister for external trade, Juan Carlos Baker Pineda, in an interview with BBC.

Another important factor affecting the North American strategic objective of building resilient supply chains, is the flow of imports of intermediate products—that serve as components in the production of a final good—from China to Mexico. While the monthly value of Chinese intermediate imports to Mexico has risen in the past five years, its share has remained fairly stable. In 2019, China constituted 19.8 percent of Mexico’s imports of intermediate goods, with its share rising only slightly (to 21.0 percent) by 2023. The US is by far the largest source of Mexico’s imports, representing 44.3 percent of its imports of intermediate goods. Recently, Vietnam and Brazil have also seen steep increases in their shares of total intermediate goods imports flowing to Mexico, though their shares remain low (2.3 percent and 1.6 percent, respectively).

Mexico’s Imports of Intermediate Goods in 2023, by Origin (billions of USD)

In sum, the single country that contributes most to Mexico’s economy and production is still (and by far) the US. While Mexico has seen a rise in capital coming from China, this rise is not unprecedented among developing countries in the Global South. Focusing on Mexico’s relationship with Asia, Japan (which experienced its spurt in investments into Mexico in the early 2010s) remains the main source of FDI flowing to Mexico. China’s presence in Mexico’s production can be mainly perceived in its relatively high share of Mexico’s intermediate goods imports, with over a fifth of Mexico’s intermediate imports originating in China. However, this share has remained relatively stable in recent years, while Mexico’s imports of intermediate goods from other Asian countries (such as Vietnam and Thailand) have grown rapidly. Recent estimates confirm that Mexico’s exports contain more than half of North American value-added. Though this depends on the industry, type of good, and manufacturer, there is no doubt that goods imported by the US from Mexico contain more North American value than goods imported from China. Comparing these two types of goods in the same category of imports is, therefore, misleading.

There is little doubt that the new president-elect Sheinbaum will have to display considerable care in navigating Mexico’s relationships with China given the importance of the US to her country’s economy. Yet, the favorable conditions driving capital (including Chinese capital) into Mexico are likely to persist, and the truth remains that the goods labeled as “Hecho en México” are, by all means, made in Mexico.

The content of this article is the exclusive property of the North Capital Forum. The author of the article retains full responsibility for the text. Any unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or use of the content without prior permission from the North Capital Forum or the author is strictly prohibited. If you wish to reference or quote from this article, please ensure proper attribution and use direct quotes.